Rubirosa, Dodgeball & The Unraveling Of Our Local Neighborhoods (Cafe Society Dinner Discussion #13)

The neighborhood community bundle kept CAC low, LTV high for local business & in return you got community. Not anymore.

Cafe Society is Maxwell Social’s weekly magazine on the intersection of community and society — an anthropological look at the underpinnings of what makes the world tick, written by David Litwak (@dlitwak) and the Maxwell team.

I had been working and marinating on this essay for four months when I saw this tweet last week from Scott Belsky:

I’ve been obsessed with this idea of the degrading local community, and how to fix it, for a while now — and today we’re going to discuss it.

For the past 30+ years we’ve been systematically unbundling community from our day to day in-person interactions in our metropolitan areas, and COVID is merely finishing the job. As a result brands are responding to the loss of a local customer base either by cultivating a global community through tools like Instagram, Goldbelly and Doordash to pick up the slack for business the local community is no longer providing, or ceding ground to chain stores and disappearing entirely, and customers are left searching for how to get the community that was previously included for free.

Let’s get started.

Rubirosa, Goldbelly & Instagram Famous

The first time my girlfriend’s family came into NYC to visit they mentioned how they really wanted to go to Rubirosa. At the time, I had been living in Nolita, a small but trendy neighborhood smashed between the Lower East Side and Soho in Manhattan, for about a year and I wasn’t even aware that the Italian spot 3 blocks away from me that seemed kind of standard from the outside had such a social media presence that people on the west coast knew about it.

But to my surprise, they had diligently cultivated a following of 45,000 people who liked photos of pizza’s with swirly Pesto on them.

I didn’t think much of it at the time — so what, it’s a Pizza spot that has nailed social media — but when I looked at their Instagram page recently and saw that they were promoting a link on Goldbelly, a service that “Empowers Small Shops & Restaurants To Ship Nationwide,” I was intrigued. Clearly they were able to convert some of those Instagram likes into pizza’s shipped around the nation.

The final aha moment was walking by one day and seeing this:

Rubirosa had decided that it was a more efficient use of their potential outdoor dining space during a pandemic to have 15–20 Doordash bikes on the curb instead of seated customers.

I realized that Rubirosa was the perfect encapsulation of a phenomena I’d been noticing everywhere -- the unbundling of the local neighborhood and the realignment of communities away from local neighborhoods towards new global or regional brand “tribes” that all ate the same food, subscribed to the same news, and bought the same brands.

But we’ve paid a steep price -- the local community that was once bundled into these services has vanished as they’ve spent less time building community on the block and more time building community on the internet.

Dodgeball, You’ve Got Mail & The Evil Chain As Antagonist

The chain brand coming into town and pushing out the local coffee shop, diner, book store, video store, general store or gym forms the “Inciting Incident” of enough movies that we all know the story.

In Dodgeball, national chain GloboGym tries to push out Average Joe’s locally owned gym. You’ve Got Mail is a tale of a small bookstore owner falling in love via email with the man who is launching a Barnes & Noble style chain nearby that will likely put her spot out of business.

The redeeming values of the small local bookstore or gym are well understood — community.

They are selling books or workouts, but the point these movies are making is the real benefit, the real reason why we’re sad that chains are pushing them out, is that they are pillars of the community.

The traditional neighborhood bundle might include a butcher, cafe, corner store, pub, gym, hardware store, movie theatre, ice cream shop, restaurant, bookstore or video rental spot, but regardless of the exact iteration, on top of each part of the bundle we got a little dose, a smattering of community. This bundle made up our post-college campus — the campus on which we run into old friends, make new ones and feel a sense of belonging as part of a wider community instead of anonymous consumers.

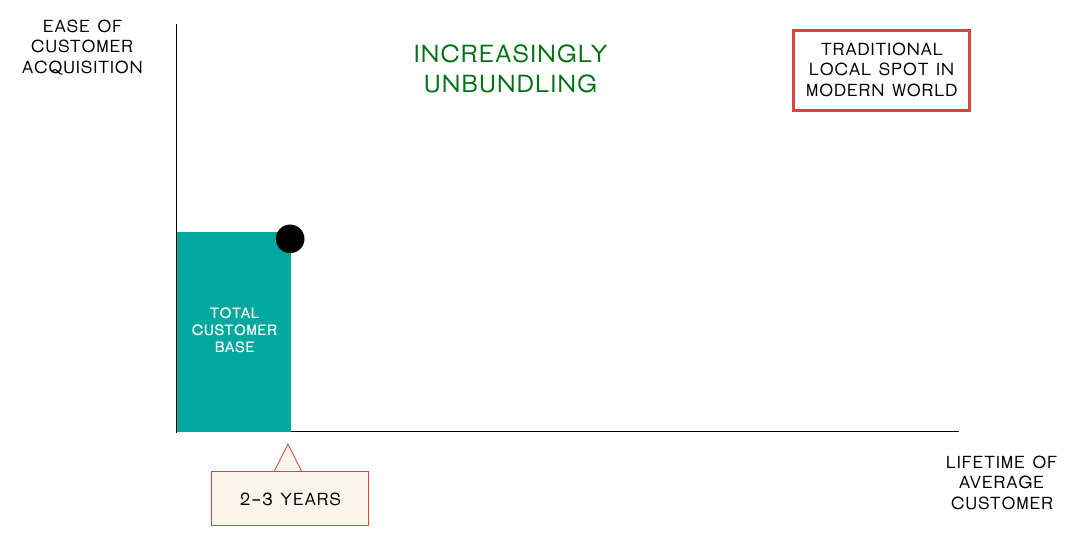

But more important was the underlying value that the community bundle provided for the underlying businesses that were a part of it — the local community kept customer acquisition costs low, after all, they were the only local pizza spot, and customer lifetime value was high, many locals became regulars for decades.

The local community was the ultimate customer acquisition and retention mechanism. It’s relatively easy to acquire customers who live in the neighborhood, after all you’re the only hardware store, pizza spot, etc. allowing you to lock down a customer for 20, 30, 40 years if you do it right.

And in exchange for giving their loyalty and business over 20–30 years, the customer received community in addition to the various city services.

This worked. While an empire building strategy it was not, small businesses could flourish with the combination of long lifetime value and ease of customer acquisition the traditional neighborhood bundle provided.

But that bargain has started to make less and less sense as the rise of chains accelerated and evolved into mass digitization.

Chains: From Harvey House to McDonalds

The transformation of our cities away from these small local community run spots has been in progress for a long time — after all You’ve Got Mail is 20+ years old.

And it has been going on for a lot longer than that — in fact, the first chain was the Harvey House, started by Fred Harvey in 1876 along the route of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. (Fun fact: he employed women because in the time of the saloon, his male employees got ragingly drunk too often).

But the real rise of chains can be attributed to McDonalds, who pioneered the modern franchise model. Since then chains have skyrocketed and are currently about 48% of the restaurants in our nation.

The value a chain brings is obvious — by systematizing brand you can minimize CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and maximize LTV (Lifetime Value) with every additional location as customers are less likely to churn and more likely to run across one of your locations, and costs go down due to economies of scale in purchasing, branding, advertising, etc. Those costs are then often passed onto consumers in the form of cheap burgers or milk shakes.

It may have taken 50+ years for chains to start becoming more prominent, but Harvey’s introduced two ideas.

One was that there was an alternative to focusing on catering to the same local customers for 30 to 40 years -- making it easier to acquire NEW customers was an equally valid way to expand the “area under the curve” i.e. total customer base, and the other was that additional locations was another way of increasing the lifetime value -- if you’re more places, you’ll have more opportunities for loyalty.

It turns out that this model was a better fit for a rapidly changing world.

An Increasingly Nomadic Population = Low LTV

A more connected world means the idea of staying 40 years at one job with a work community is unlikely, millennials jump between jobs at twice the rate as the previous generation, and home ownership rates are the lowest in 60 years among young adults.

When you factor all of this in, it literally makes less sense than it ever has to bundle in local community with your coffee, because the LTV of a particular person who comes in your bookstore or video shop or cafe might now be 2 or 3 years instead of 30 or 40.

Why invest in learning people’s names? That person is now more likely to be a random tourist or a person passing through the neighborhood who just wants a cup of coffee and you happen to be the cafe they ran across than the person who just moved in next door and will stick around and build a family in the neighborhood.

Which is how we get back to Rubirosa.

Goldbelly, Instagram & Doordash: Local Shops & Global Brands

The more global the world the bigger advantage global brands have, and the more pressure you have to either create one or fail.

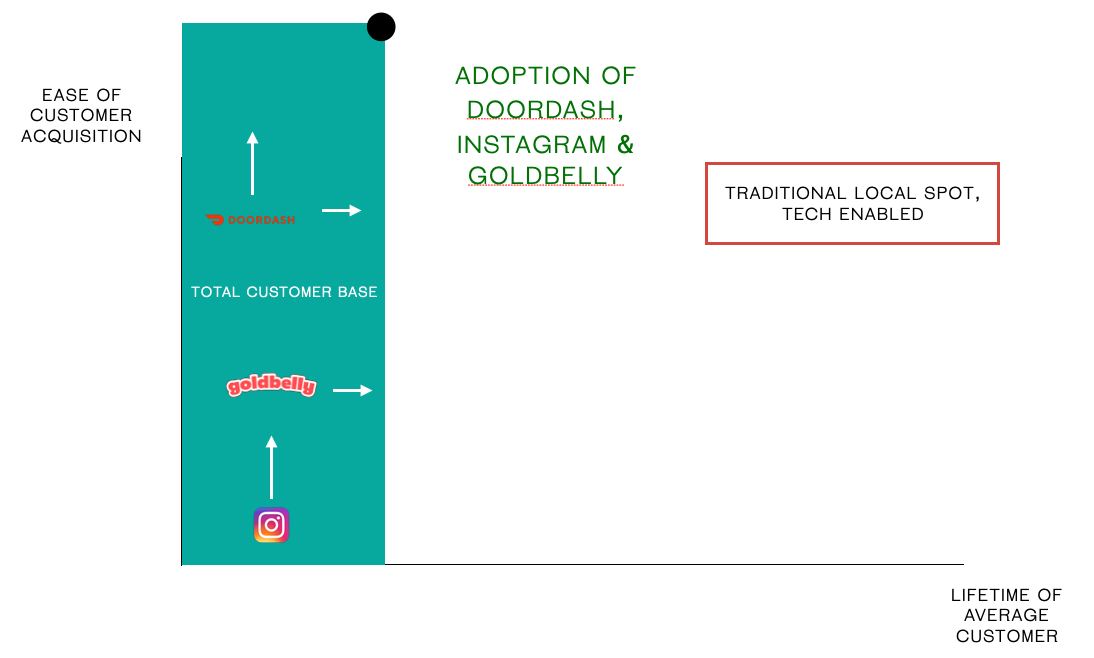

And that’s why Instagram, Goldbelly and Doordash have become so interesting — none of these shops, the Rubirosas of the world, will ever be able to compete with a Starbucks when it comes to LTV or CAC, but Instagram, Goldbelly and Doordash are putting their finger on the scales in their favor by reducing geography as a limit on LTV and and reducing the cost to acquire a new customer.

Doordash has moved “special occasion” users into the “regular” category while Goldbelly has moved the “once a year” user into the “special occasion” category.

And while there is a valid debate on the economics of food delivery apps, and whether or not they are taking advantage of local spots, they are an essential part of the new stack -- without them you’d need to be located walking distance to become a regular.

Together, a local spot like Rubirosa is able to piece together enough customers to survive.

But this isn’t great for the local community.

Recognizing that their “regulars” now include people all over NYC and not just those who decided to live in Nolita, it makes more sense to take up half the available outdoor sidewalk space in front of Rubirosa with Doordash bikes . . .

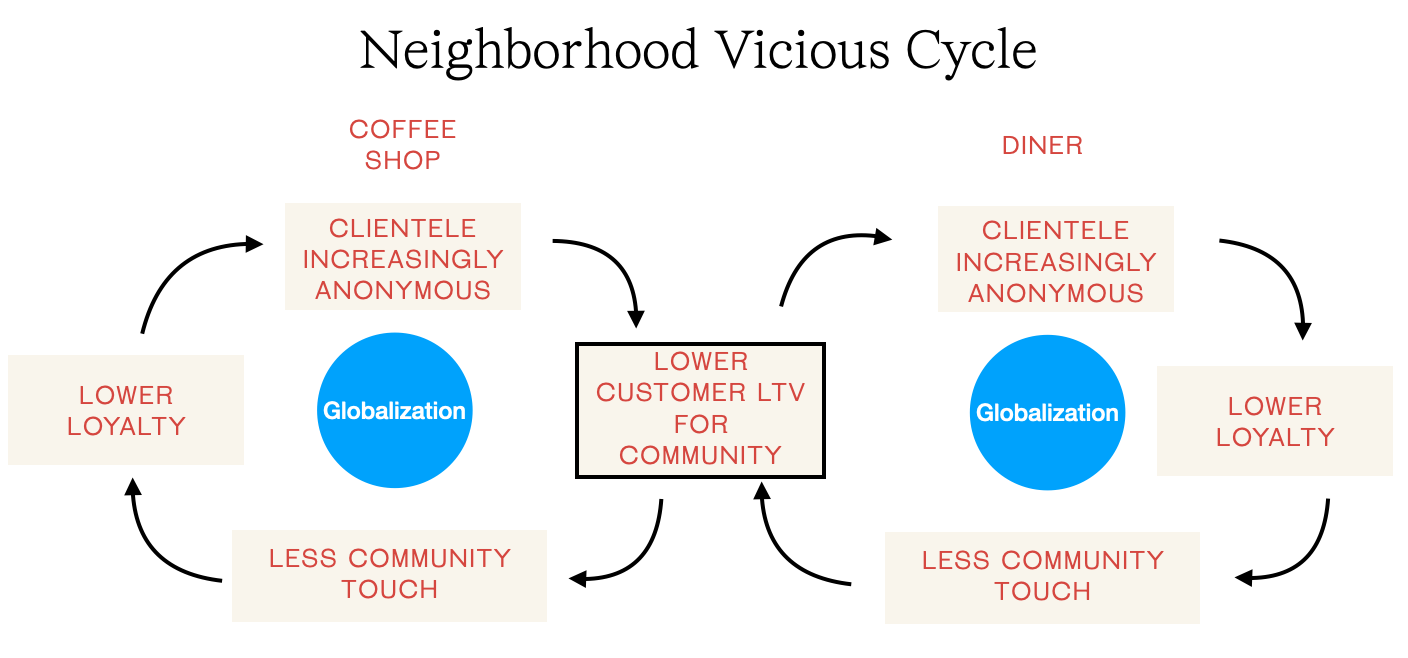

In the same way Rubirosa doesn’t even bother constructing enough outdoor space for more than 8 people, a local cafe is less likely to invest in community events if an increasing percentage of their clientele is not part of the community and the little community that’s left churns every 3–4 years.

And this compounds on a neighborhood basis — as we remove each part of the bundle of a neighborhood, we make the rest of the neighborhood/campus bundle less valuable, spurring a vicious cycle — when Rubirosa decides to basically turn their curbspace into a Doordash delivery zone, or when the cafe starts hiring badly trained employees to lower their prices to compete with Starbucks, that makes living in that neighborhood less attractive, and lowers the LTV for the local video store and the diner, not just the cafe or restaurant.

And our community bundle quickly looks like this:

Company F.C.

Up until now I could understand if you think all of this is Gladwellian correlation mistaken as causation — where is the evidence that Rubirosa has literally calculated that investing in the hyper-local community just has a lower ROI.

The clearest statistic supporting that on some gut level this calculation around investing in community is actually taking place is in the workplace, specifically around company sponsored athletic teams, which are getting rarer and rarer according to Inc:

Unfortunately, U.S. businesses that sponsor a company athletic team are turning into something of an endangered species. TheWall Street Journal reports that just 12 percent of companies nationwide have competitive athletic teams, down from 29 percent in 2007.

Company’s are increasingly abandoning community building among their employees — as employees move from job to job more frequently, investing in camaraderie seems to be making less and less sense — with the LTV of a community member getting lower and lower, it simply doesn’t pay dividends.

Destruction 2.0: Mass Digitization

As this vicious cycle reaches its natural conclusion and erodes the one true benefit of local commerce, the community, the logical conclusion is to go the full monty and just digitize everything, and that’s exactly what has started to happen. Whatever “Third Place” marketing Starbucks may espouse, they aren’t content to just replace the local cafe with their own cafe, they are moving to kill the cafe part of their offering all together:

“Championing speed and convenience, CEO Kevin Johnson is doubling-down and accelerating the construction of hundreds of drive-thrus and 40 to 50 urban pickup-only stores. In other words: shifting from the experiential model that made Starbucks Starbucks, to that of a glorified food truck.”

Starbucks has realized the above cycle means you need to go one direction or the other, and they’ve mostly chosen digitization.

And they aren’t alone. Working out used to be the purview of Average Joes, became GloboGym (24 Hour Fitness, Planet Fitness), and now is in your home with Peloton.

Last month, Airbnb rented out the final Blockbuster as a gimmick — you could stay overnight in Bend, Oregon to relive your 90s video store perusing experience because now, of course, you can just stream Netflix and rent on Amazon Prime. Doordash & Instacart are making it possible to literally stay in our homes for everything food related.

One of the last vestiges of community was our workplaces, but those have transformed from spots where you got a gold watch after 40 years on the job, to changing jobs and cities every 2–4 years to increasing numbers of 1099 Freelancers, to now a full embrace (COVID aside) of remote work via Slack.

As this cycle has played out, we’ve taken it to its natural conclusion but with it, our sense of community has been thrown out too. Mass digitization has finished the job and killed the last remnants of the traditional neighborhood bundle for the average urban American, and left us to pick up the parts.

There is a famous quote by Jim Barksdale:

“There are only two ways to make money in business: One is to bundle; the other is to unbundle.”

Over the next few months, the “re-bundling of the local neighborhood” is going to be a key theme of this newsletter. I believe the key to answering Scott’s question is to figure out how to bring community back as a key part of of the local business bundle.

Stay tuned.

David (@dlitwak) & The Maxwell Team